GALLERY OF LEGUMINOLOGISTS

Janet Sprent (1934–)

Compiled by Euan James, Julie Ardley, Colin Hughes and Peter Young

Janet I. Sprent received a BSc, Associateship of the Royal College of Science (ARCS) from Imperial College London in 1954, a PhD from the University of Tasmania in 1960, a DSc from London University in 1988 and an honorary Doctorate in Agriculture from the University of Uppsala (Sweden) in 2006. Most of Janet’s academic career was spent as a professor at the University of Dundee in Scotland where she is now Emeritus Professor of Plant Biology.

Janet Sprent in Tasmania, 2019. Photo: Julie Ardley.

Janet Sprent in Tasmania, 2019. Photo: Julie Ardley.

Through her extensive research career spanning more than 50 years, Janet became a leading world authority on legume nodulation and nitrogen-fixation. She travelled widely, conducting field research in many countries, including Kenya, South Africa, Australia and Brazil. A major focus of Janet’s research has been to relate legume taxonomy and evolution to microsymbiont taxonomy, and throughout her career she collaborated extensively with the legume systematics community, contributing evidence from nodulation to the understanding of legume evolution, and always eager to see the latest legume phylogenies and what they say about nodulation. Janet’s work also addressed practical problems through more applied research, such as the development of novel drought-resistant legumes for the wheat belt of Australia; this has led to the naming of one of the rhizobial inoculants that is used, in her honour, as Paraburkholderia sprentiae. Janet is a long-standing member of British Ecological Society (BES), a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE), and was latterly a Trustee of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh. She has published more than 500 peer-reviewed papers since the mid-1950s, many of them pioneering studies on legumes and other symbiotic plants. Janet has also published four books that became standard textbooks on the N-cycle, legume nodulation and N-fixation spanning all levels from high school upwards.

Sprent (2001) and Sprent (2009) are standard texts for nodulation in the Leguminosae.

Sprent (2001) and Sprent (2009) are standard texts for nodulation in the Leguminosae.

Indeed, Janet is a remarkable communicator able to cross cultural and educational boundaries and she has been particularly committed and effective in mentoring, supervising and helping scientists in the developing world, especially women, thereby contributing a legacy of expertise on nodulation around the globe. Her endeavours in education were recognized by her award of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1996. Janet has always been enthusiastic about joining legume experts from different fields, particularly encouraging collaborations between legume systematics and nodulation research, and playing a leading role in the international legume community. Indeed, her spirit of scientific integration and international collaboration epitomises the essence of the International Legume Conferences, the most recent of which in Pirenópolis, Brazil, in 2023 honoured her contribution by dedicating a session on symbioses to her.

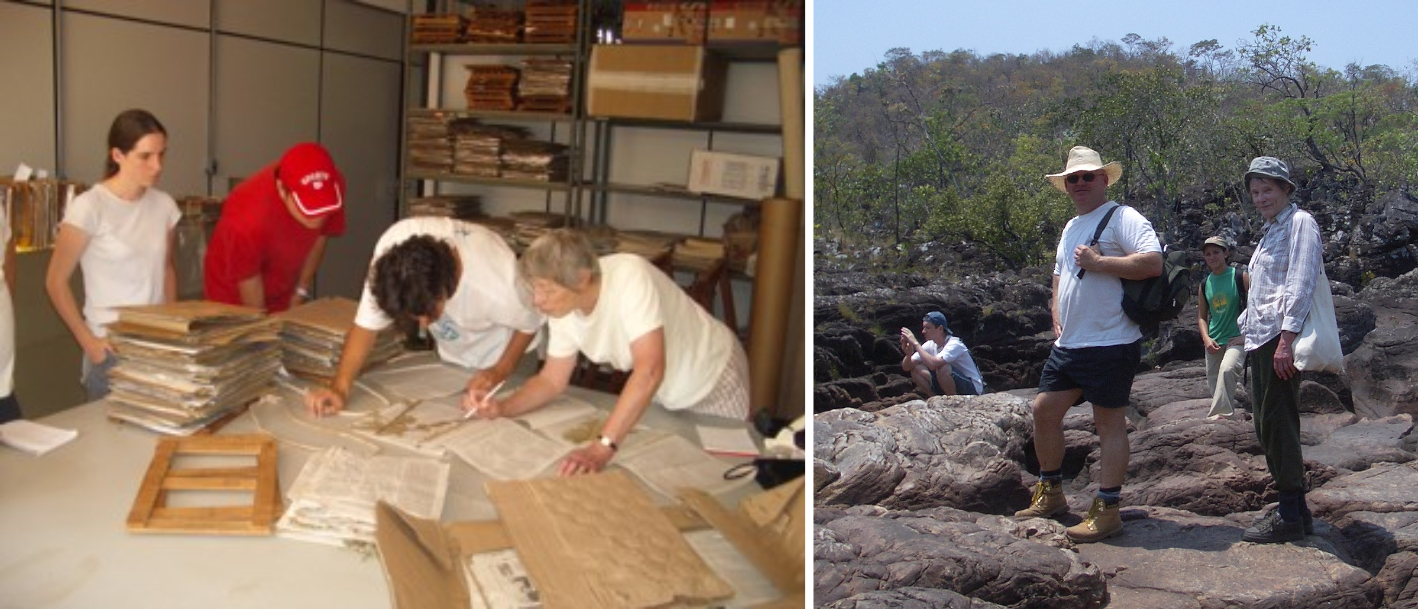

Left to right: Janet Sprent at the Embrapa-CENARGEN herbarium, Brasilia, in September 2005 examining voucher specimens of Mimosa spp. Janet Sprent and Euan James in the Chapada dos Veiadeiros National Park, Goias, Brazil in September 2005. Photos: Peter Young.

Left to right: Janet Sprent at the Embrapa-CENARGEN herbarium, Brasilia, in September 2005 examining voucher specimens of Mimosa spp. Janet Sprent and Euan James in the Chapada dos Veiadeiros National Park, Goias, Brazil in September 2005. Photos: Peter Young.

Josephine (Jo) Kenrick (1929–)

Compiled by Peter Bernhardt and Helen C.F. Hopkins

Jo Kenrick worked in the School of Botany at the University of Melbourne in Parkville, Australia. Many of her early publications, often in collaboration with R. Bruce Knox, were on the pollen and stigmas of Acacia, including a major overview of pollen-pistil interactions in mimosoid legumes in Advances in Legume Biology in 1989, and she also published on the pollination of Acacia species in Victoria. She received an MSc in 1982, followed by a PhD in 1994. Although she is probably best known for her studies on Acacia, as part of a pollen and allergen research group, her interests later extended to other plant families. The following reminiscences have kindly been contributed by Prof. Peter Bernhardt of St. Louis University, U.S.A.

“When I think of Jo Kenrick I think of precision. Who else had the patience and determination to develop the skill of removing a polyad from an Acacia anther and depositing it flat on the narrow receptive surface of the stigma? To compare pollination in nature, Jo fixed entire inflorescences of Acacia species and observed each one under a microscope to see which stigmas bore polyads. She even found a few natural examples of two polyads in one stigma cup because they were deposited vertically. I was blown away by her first fluorescence micrographs showing pollen tubes germinating from each grain in the polyad then growing down the style and unravelling so each tube found one ovule. As the female phase in all the florets in an Australian Acacia inflorescence is synchronous, Jo often hand-pollinated more than one stigma in the same head or spike producing multiple pods which you rarely see under natural conditions.

Left to Right: Jo Kenrick at the Flora of Australia Acacia Workshop, Melbourne, 1983, and at Paradise Falls, Victoria, Australia, 1985, photos Bruce Maslin.

Left to Right: Jo Kenrick at the Flora of Australia Acacia Workshop, Melbourne, 1983, and at Paradise Falls, Victoria, Australia, 1985, photos Bruce Maslin.

“Dr Kenrick and I finished post-graduate degrees within a few years of each other but she was among the first to be hired by the late Professor R. Bruce Knox (1938–1997) to work in the new Plant Cell Biology Research Centre at Melbourne University. Both of us were assigned initially to the Acacia reproduction division and Jo was the kindest of all coworkers. She added me to a study on a seaside population of Acacia retinodes growing by a golf course at Cape Schanck. She did the hand pollinations while I caught the pollinators. She discovered that these large shrubs cloned themselves with woody runners under the sand. Now she could do both crosses between clones to compare self-incompatibility results versus outcrossed individuals. We had to leave early in the morning as the receptive stage in Acacia stigmas is early and very brief. I’d take a tram to her house before we headed off and she would have a hot breakfast waiting for me and she's the ONLY person who ever made me kedgeree. We also discovered a bakery along our route to Cape Schnack that made the best brandy snaps. We became regular customers for the duration of the fieldwork.

“Many Australian acacias bloom during the winter and I remember Jo taking us to the edge of the Little Desert just before dawn. The stems of spiny, prostrate species wore long, needle-crystals of hoar frost. As the sun rose, we watched those crystals sublimate and vanish.”

“Jo organized several expeditions within the state of Victoria while she headed the Acacia Reproductive Biology programme within the Plant Cell Biology Research Centre. This was of interest to other schools within Melbourne University and certain government agencies. There was an agricultural element to see if native acacias could serve as green manures and whether their root nodules added appreciable amounts of nitrogen to soils. A horticultural division expressed an interest in some of the spiniest species that might serve as "anti personnel" plants around buildings. There was even talk about the nutritional aspects of Acacia seeds based on a history of indigenous women pounding them into cakes.”

“Fieldwork on Acacia terminalis s.l. in Gippsland, Victoria, posed new challenges to Jo. Depending on the population, this species can produce a large, red extrafloral nectary at the base of its petiole. As inflorescences appear at the base of the leaf, this suggested bird-pollination. Jo and her assistants learned to mist-net, band and release birds after taking instruction from local experts. To see if the bird was carrying Acacia polyads when caught, she rubbed the beak and head feathers with a cube of glycerine jelly stained with basic fuchsin. The cube was placed on a glass slide under a cover slip. She found the best way to liquify the cube, exposing the exine to the stain, was to warm the slide with the cigarette lighter in the dashboard of the university vehicle she had signed out for the trip. Acacia terminalis blooms during cold, wet April in Gippsland. While the mist net was checked, frequently some of the birds (tiny thornbills and silvereyes) were obviously shocked by entrapment and handling as well as by the cold, moist season. I would return from insect-collecting to find Jo and her assistants warming the birds under their coats and giving them drinks of glucose and water. Mosquitoes were thick in this woodland and we were surprised to see the same birds, once warmed and recharged, would often eat the dead mosquitos we swatted and offered before releasing them.”

Suzanne Koptur (1955–)

Compiled by Helen C.F. Hopkins

Suzanne Koptur is an ecologist and botanist with a wide interest in plant-animal interactions. Although she has not worked exclusively on legumes, she has had a long and enduring association with the family and has published on genera in all three of the traditionally recognized legume subfamilies. Her research covers mutualisms with ants and the role of extrafloral nectaries in plant defence, floral biology, breeding systems and pollination ecology, and the biology of caterpillars as herbivores.

For her PhD at UC Berkeley, Suzanne studied the floral biology, breeding system and phenology of many species of Inga, and their pollination by a variety of organisms including sphingid moths, hummingbirds and butterflies in the forests of Monte Verde in Costa Rica. Her hand-pollination experiments revealed that, for two species, cross-pollinations between individuals of the same species were not compatible unless the parent trees were separated by 1 km or more. This work was under the umbrella of a larger study of the phenology of cloud forest trees and shrubs and was supervised by Herbert Baker and Gordon Frankie. For good measure, she also studied the interactions among Inga’s herbivores and the insects attracted to their foliar nectaries.

Left to right: Suzanne in the Everglades National Park, Florida, photo Hipolito Paulino Neto, and with a non-legume, Guettarda scabra, 2014, photo John J. Koptur-Palenchar.

Left to right: Suzanne in the Everglades National Park, Florida, photo Hipolito Paulino Neto, and with a non-legume, Guettarda scabra, 2014, photo John J. Koptur-Palenchar.

As a NATO-funded postdoc with John Lawton at York University in the U.K., she used artificial defoliation experiments in an allotment garden to explore the effects of herbivores on Vicia sativa. Untangling the interactions among ants and parasitoids that visited the stipular extrafloral nectaries, she found that the ants prevented the parasitism of herbivorous moth larvae that feed inside the developing fruits. The study continued in subsequent summers with support from the British Ecological Society, comparing the plant/herbivore/parasitoid interactions of two species with extrafloral nectaries (V. sativa and V. sepium) and two without (V. cracca and V. hirsuta).

In 1985 she joined the faculty of Biological Sciences at Florida International University (FIU), where she taught courses in botany and ecology. The genera she and her many postgrad students have studied included Centrosema, Chamaecrista and Senna, with much of the fieldwork done in southern Florida. She also conducted research as a Fulbright scholar in Mexico, on ferns with foliar nectaries, in collaboration with Victor Rico-Gray and colleagues at the Instituto de Ecologia in Xalapa in 1994 and again in 2009, when she and her family spent six months living in the Pueblo Magico of Coatepec.

Retiring in August 2021, Suzanne is increasingly involved with local plant and insect societies, also finding time for gardening and other creative ventures. But she continues to work on the pollination of plants in the pine rocklands and on the effects of urban areas on plants and animals in habitat fragments, and she is writing up projects whose publication has been delayed by the demands on a professor’s time. She reports that two of her final PhD students have recently completed, with one more to go! – Andrea Salas, who is investigating the potential for a native plant, Senna mexicana var. chapmanii, to serve as an insectary in the cultivation of fruits and vegetables in south Florida agriculture.

References

Bernhardt, P., Kenrick, J. & Knox, R. B. (1984). Pollination biology and the breeding system of Acacia retinodes (Leguminoseae: Mimosoidae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 71: 17–29.

Kenrick, J. & Knox, R. B. (1989). Pollen-pistil interactions in Leguminosae (Mimosoideae). In: C. H. Stirton & J. L. Zarucchi (Eds.), Advances in Legume Biology. Monogr. Syst. Bot., Missouri Bot. Gard. 29: 127–156.

Knox, R. B., Kenrick, J., Bernhardt, P., Marginson, R., Beresford, G., Baker, I. & Baker, H. G. (1985). Extra-floral nectaries as adaptations for bird pollination in Acacia terminalis. Amer. J. Bot. 72: 1185–1196.

Koptur, S. (1983). Flowering phenology and floral biology of Inga (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae). Syst. Bot. 8: 354–368.

Koptur, S. (1984). Outcrossing and pollinator limitation of fruit set: breeding systems of neotropical Inga trees (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae). Evolution 38: 1130–1143.

Koptur, S. (1984). Experimental evidence for defense of Inga (Mimosoideae) saplings by ants. Ecology 65: 1787–1793.

Koptur, S. (1985). Alternative defenses against herbivores in Inga (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) over an elevational gradient. Ecology 66(5): 1639–1650.

Koptur, S., Jones, I. M. & Peña, J. E. (2015). The influence of host plant extrafloral nectaries on multitrophic interactions: an experimental investigation. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138157. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138157

Marquis, R. J. & Koptur, S. (2022). Caterpillars in the Middle: Tritrophic interactions in a changing world. Springer.

Oliveira, P. S. & Koptur, S. (2017). Ant-Plant Interactions: Impacts of humans on terrestrial ecosystems. CUP.